Eclipse Special! Moon on Track to Intercept Sun

- Douglas MacDougal

- Oct 8, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 24, 2023

It would be refreshing if newspaper headlines reported current astronomical events this way. Think what it would do for collective awareness of the natural world. The subheading might read,

“Moon too far away this time to fully cover our sun.”

On Saturday, October 14, 2023, an annular solar eclipse will be visible in North America. The “ring of fire” appears first in the early morning in Oregon. Its track then slants sharply southeast through Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, and Texas before slicing through the Gulf of Mexico, across the Yucatán Peninsula, over Columbia and the Amazon basin, and ending in the Atlantic Ocean. The phenomena will last 5 minutes and 17 seconds at its maximum over Costa Rica, but the duration will be shorter in other places – for instance a minute less in Oregon.

The big event is an annular eclipse. (Note, that’s not “annual”). The word comes from the Latin annulus, which means “ring.” The moon, at a hefty 397,017 kilometers away, floats past its apogee (from Greek, meaning “from earth”) just four days earlier, on the 10th, and becomes too small in angular size to fully blot out the sun. Hence, a dazzling ring of sunlight surrounds the moon’s dark disk at mid-eclipse. The sky won’t darken as during a total solar eclipse, but brilliant Venus should be visible to the west of it, and perhaps even Mercury.

The basics

I didn’t talk much about this particular annular eclipse in previous posts, nor will I in my upcoming article in Sky & Telescope magazine’s January 2024 issue which focuses much more on April’s total solar eclipse whose path traces up from Mexico and across to the Northeast USA. So, I thought I’d take a moment here in the form of this brief bulletin and refresher to help catch you up on the nuts and bolts of this event.

Eclipses that are a little more than 18 years apart share a similar geometry: each path is parallel but shifted east. So, the annular solar eclipse track of October 3, 2005, over Africa, for example, slants parallel to ours of October 24, 2023, centered over Central America, which will likewise track parallel to the annular solar eclipse of October 25, 2041, over the Pacific Ocean.

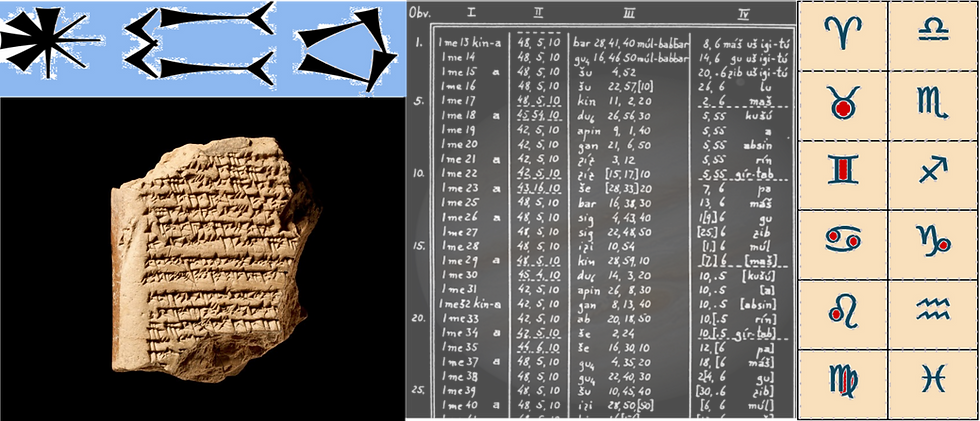

This saros interval of 18 years, 11 1/3 days, includes many dozens of eclipses which are grouped by number. The upcoming eclipse is in solar saros series 134, a group that began on June 22, 1248, around the time the foundation stone was placed for the great gothic Cathedral in Cologne (completed, by the way, about five and a half centuries later, almost midway through the series). It will end on August 6, 2510, when those who have come after us have managed – we hope – to be good stewards of our small planet. Overall, this saros 134 consists of 71 eclipses in 1262 years.

This annular eclipse in saros 134 is the tenth out of a string of 30 consecutive annular eclipses that began in 1861 and which will conclude in 2384. A large number of annular eclipses in a saros series is fairly common. Saros 132 and 140, for example, have over 30 annular eclipses each. Saros 138 has 50 annular eclipses. On the other hand, saros 130 has none.

Eclipse lineup

You can see the crescent moon approaching the sun in the early morning hours this week, with the moon dropping almost vertically downward past Venus toward Mercury and the sun. The moon’s slender crescent will become lost in the glare of the sun a few days before. To see the configuration from where I live in Portland, Oregon, I went into Stellarium, that amazing bit of free planetarium software, and displayed the image below of the configuration of the moon eclipsing the sun, with Mercury above and Spica (in the constellation of Virgo) and Mars below. I subtracted the atmosphere and its glare, which we can’t do in real life. What a beautiful configuration of stars and planets! The question is, how much of these will we be able to spot during the eclipse with its brilliant ring.

The other node

Solar eclipses that have even saros numbers are descending node eclipses. (You can consult the chart at https://www.douglasmacdougal.com/post/in-search-of-the-perfect-solar-eclipse to sort out the numbering.) That means the moon is moving down in its tilted orbit across the ecliptic plane when the eclipse occurs, and the moon creeps northward with each eclipse in the series (as the value of gamma discussed in my last post increases). Saros 134 thus began near Antarctica and the last eclipse in the series will bid us farewell near Greenland.

Since this is a descending node eclipse, where is the other node? The ascending node is exactly on the other side of the moon’s orbit. Six months from now the sun and moon will be aligned at the ascending node for the total solar eclipse of April 8, 2024. Then the moon will be only one day past its perigee (on April 7th), its closest point to earth, and will amply cover the sun’s disk.

Interestingly, the southwest to northeast path of the April 2024 eclipse path will cross the northwest to southeast path of the October 2023 eclipse. Where will they cross? Is there a place in the country where you don’t need to travel to see both eclipses? The answer is, yes! It’s in Texas, not far northwest of San Antonio. See you there!

Comments